How to build a scene?

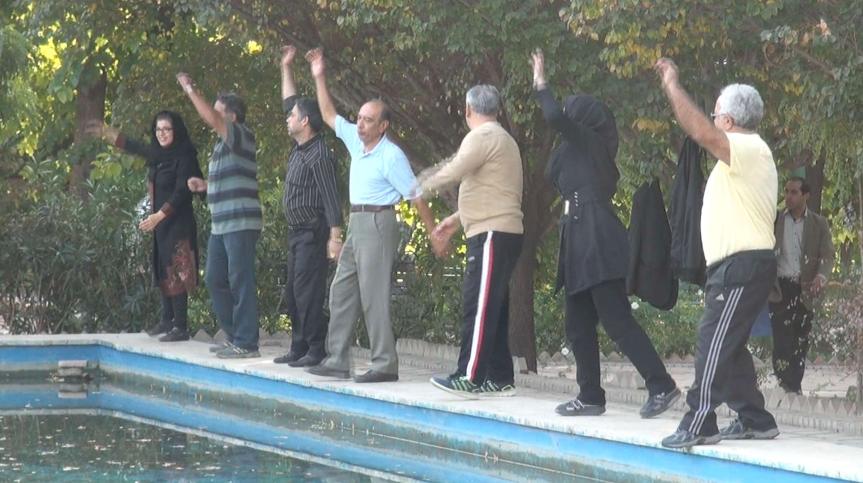

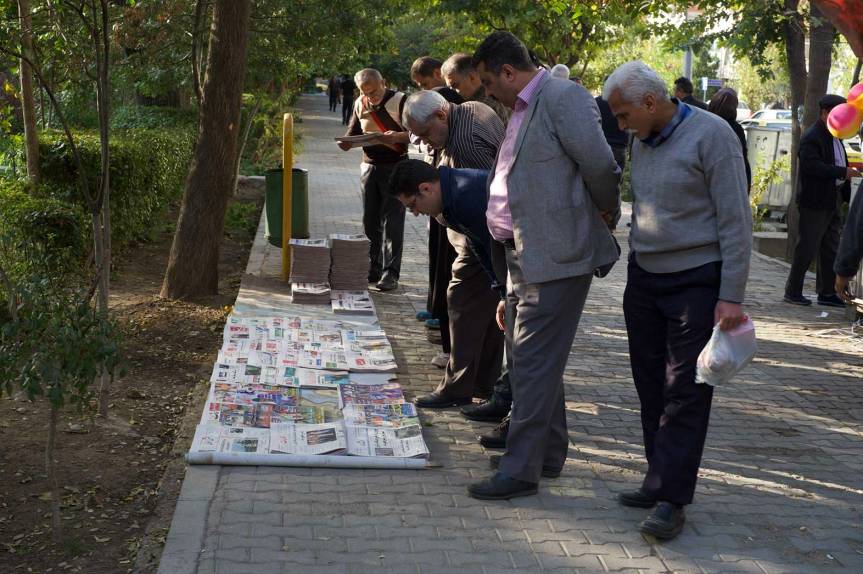

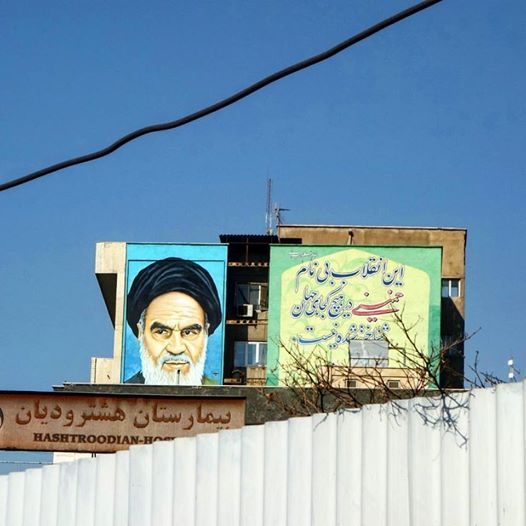

In Isfahan the air was cool and fresh. The city felt vibrant and easy-going, and there was music in the public park of the river-bed. But we were also told that Isfahan is in fact more religious and conservative than Tehran, and there were indeed more black chadors and religious scholars to be seen in the streets of Isfahan as signs of a strong religious presence. This was being backed up by black flags waving everywhere in the streets to mark the 37th anniversary of the takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran by student activists in 1979, an annual rite of anti-Americanism. But the city still had an easy feel to it.

Everybody we talked to in Isfahan mentioned the need for a central player that could somehow act as an engine for the art scene of Isfahan. Even though the city has a history of being the cultural capital of Iran with magnificent architecture and a strong arts and crafts tradition, there is apparently today a lack of a central hub that could facilitate network, exchange and a discoursive background for the contemporary artists living and working in Isfahan.

The Isfahan Museum of Contemporary Art (IMCA) used to be the dressing house for the royal family who resided in the nearby palace (What a great idea to have a giant walk-in-closet in the back of your garden!). The building now belongs to the municipality of Isfahan, who also funds the activities of the museum. The building seems to need some love and tender care, and there also seems to be some confusion about the ‘contemporary’. A sign showed the way to ‘The Present Past’, but the present present was not so easily found.

The museum has an ambitious plan of creating the ‘Isfahan Forum of Visual Arts’. This forum would act as a centre point through joint organizational programs, inviting all relevant players from the art scene of Isfahan to join in. This may sound like a brilliant idea in theory, but it is not so easy to pull off in reality. There seems to be some scepticism towards initiatives from governmental institutions. So before anything the institution may need to gain trust from the artists and art professionals of the contemporary Isfahanian art scene first.

CC Art Space (Centre for Contemporary Creation) is the new kid on the block. Located in a nice and lively residential area where small shops lie next to busy workshops, we found the brand new and crisply renovated space. The focus of CC is to bring together people from various fields of creation by presenting interdisciplinary art practices. The space just recently opened with a solo show of Mahmoud Bakhshi who is probably the most well-known and acknowledged Iranian artist internationally. The show was beautifully installed and the framed slabs of black concrete resonated powerfully with the flapping black flags in the streets of Isfahan.

CC Art Space has the double ambition of connecting the contemporary art scene and developing the discourse of contemporary art in an Iranian context by having workshops and other forums for discussion. And at the same time to not just look inward, but also connect with the surrounding society, developing them as an audience. They do this cleverly by working together with architects and designers whose work is somewhat closer to the everyday lives of people. And by servicing local schools, providing first-hand experiences with contemporary art for the local school kids. They also finance their activities partly from renting out the upper space of the building to a visual communication agency.

We also spoke to VA Space for Contemporary Art, which is an independent art space without a physical place. The two driving forces Mona Aghababaee and Samira Hashemi also sensed the need for a hub back in 2014 and created VA in response to foster creative thinking and collaborations by connecting artists, curators, critics and writers through workshops, talks and projects nationally and internationally. VA is informally organized and pop up with activities around the city of Isfahan and elsewhere, and they now also run a residency programme to underline the importance and focus of exchange.

And then we were off for some serious bazar shopping and mesmerizing mosque sightseeing around the Naghsh-e Jahan Square, before hitting the road back to Tehran again.

Tine Vindveld